– Advertisement –

By Gaia S Child

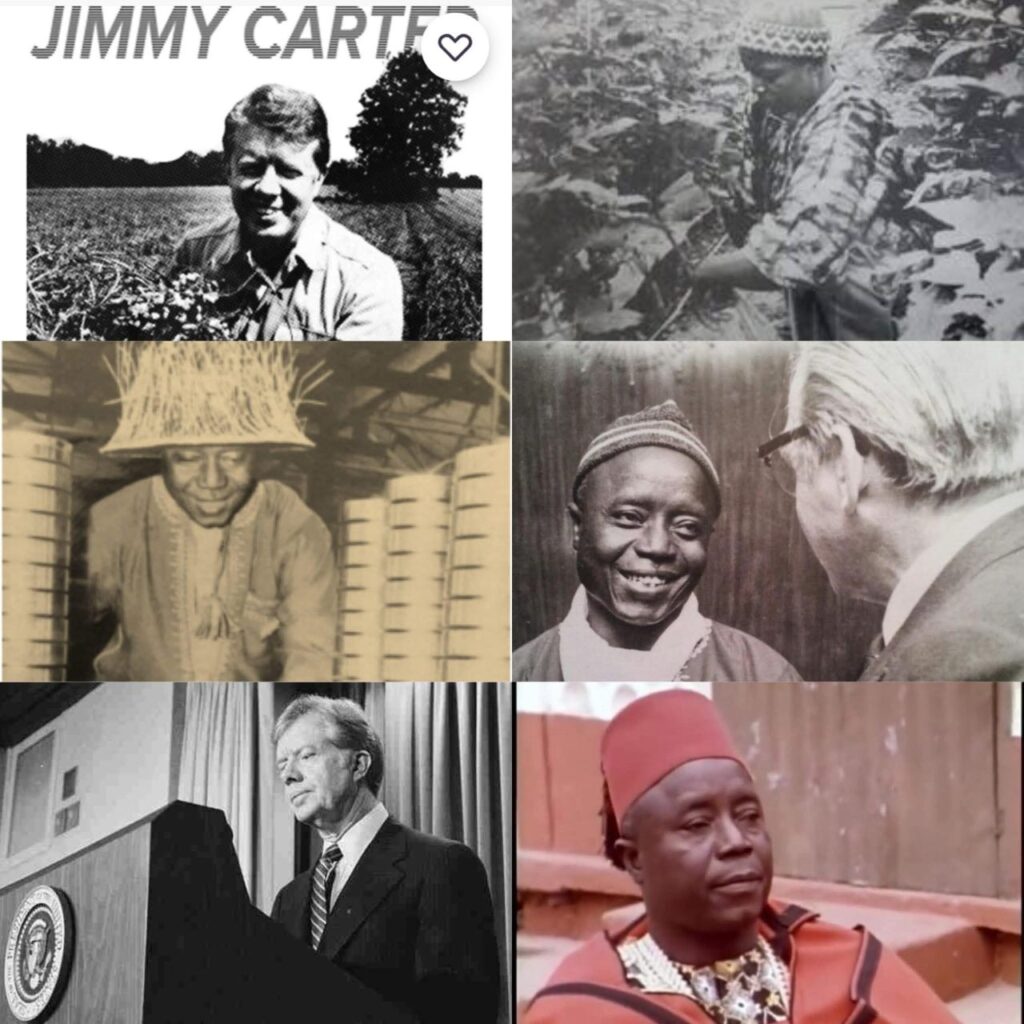

When President Jimmy Carter, the world’s most famous peanut farmer, invited him to America, Sanjally Bojang smiled and declined. “It is too difficult for a farmer to leave his crops and his land,” he said. That single sentence from his farm in Kembujeh captured everything about the man, rooted, loyal, and quietly proud. He was content to let the soil be his stage and the wind his witness. For him, true greatness was not about being seen but about belonging. His life was a hymn to humility, proof that a man could shape history without ever leaving home.

The Peace Corps volunteers who met him described a man at peace with creation. They found him standing guard over his maize, sling in hand, as the weaver birds circled above. When told to kill them, he refused, saying gently, “I don’t like that kind of killing. The birds were here before I came.” He spoke as one who understood balance, that life, like land, must be shared, not conquered. He walked his fields with the patience of a man who knew every tree by name. His ponds, once just spring-fed hollows, now teemed with fish he had raised himself. When a vine fell into the water, he watched the fish nibble at its leaves and smiled as though they were old friends. In that moment, the Peace Corps writer noted, it felt as if even nature paused to listen to him.

– Advertisement –

Before he was remembered as a farmer, Sanjally was the quiet kingmaker of Gambian politics. He was the man who stood behind the movement that became the People’s Progressive Party, helping to bridge the gap between the protectorate and the colony. When Jawara was still a young veterinary officer, it was Sanjally and a few trusted elders who saw the leadership spark in him. They approached him with humility and conviction, setting in motion a partnership that would define a generation. Their bond was mutual respect, one led with intellect, the other with instinct. Years later, Jawara would reflect that without men like Sanjally Bojang there would have been no movement strong enough to unite the protectorate and give voice to the people’s hopes.

He spoke in broken English, but his meaning was never broken. His humour and humility softened even the hardest hearts. Villagers still remember him saying, “I no talk plenty, but I watch plenty.” That was Sanjally, observant, thoughtful, never quick to judge. As Chief of Kombo Central, he ruled with patience and fairness. But life, as it does to the purest souls, tested him. During the coup attempt of 1981, he was among those forced at gunpoint to denounce Jawara on the radio. It was a moment that wounded his spirit but not his dignity. When stripped of his chieftaincy, he returned to Kembujeh without bitterness. He farmed again, taught patience through example, paid the school fees of children who were not his own, and still found time to mediate quarrels among neighbours. His silence after disgrace was more powerful than the speeches of those who condemned him.

Sanjally Bojang died in 1995, leaving no monuments or marble statues behind, only the quiet fragrance of integrity. He was the bridge between the people and power, the builder of trust, the man who never sought credit yet carried the weight of a movement on his shoulders. His trials became his testimony, his humility became his crown. The story of The Gambia cannot be told without him because he lived at its roots, planting, nurturing, forgiving. And as long as maize still grows in Kembujeh and the weaver birds still sing above his ponds, the spirit of Sanjally Bojang, the quiet kingmaker of Gambian politics, will live forever in the wind.