Courtesy|Human Rights Watch

People with disabilities in South Sudan continue to face major obstacles in their daily movement, with poor road conditions and limited traffic awareness restricting access to education, work, healthcare, and public life.

Despite ongoing advocacy from disability groups, inclusive infrastructure and accessible traffic systems remain scarce, and many citizens have little understanding of mobility needs for people with disabilities.

Individuals from the visual, physical, and hearing disability communities told Eye Radio about the challenges they face navigating the streets of Juba and other towns.

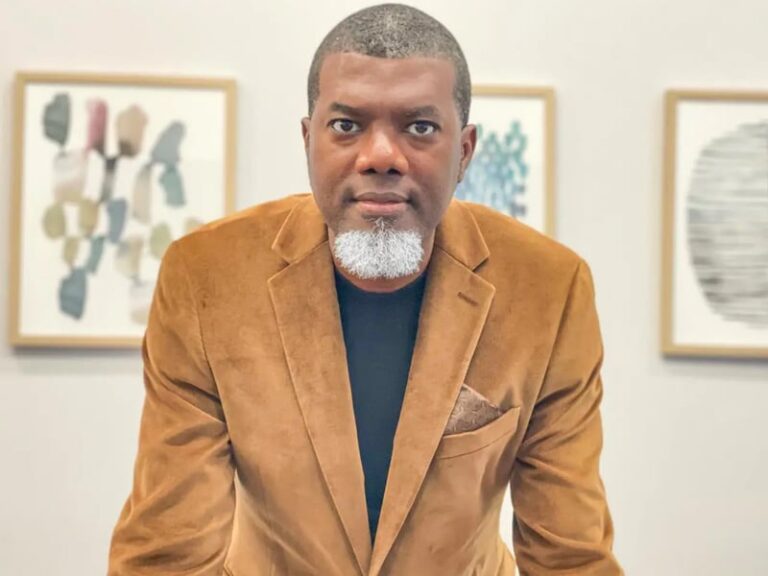

Seme Lado Michael, Secretary General of the Union of Physical Disability Centre in Equatoria State, says many people with physical disabilities risk their lives when crossing roads.

He said that some live with more than one disability, making mobility even more difficult. He recalls an incident where a person who crawls was struck by a passing vehicle.

“The driver tried to flee, and when confronted, he said he didn’t believe the person was a human being,” he says.

Seme observes that while some drivers allow wheelchair users to cross, others drive past without slowing down.

He calls for stronger cooperation between disability groups and the traffic department, adding that disability needs are not reflected in current traffic rules.

He also notes that several traffic signs in Juba have faded or disappeared, leaving vulnerable road users without vital protection.

For the visually impaired, movement is equally difficult. Issa Khamis Mursal, Deputy Chairperson of the South Sudan Association of the Visually Impaired, says sidewalks meant for pedestrians are often occupied by vehicles.

“Drivers park on the sidewalks, which we blind people use for walking. Sidewalks are our safest passage,” he says.

Issa adds that many motorists do not understand white cane signals, leading to avoidable collisions.

He says several members of the visually impaired community have been hit by vehicles because drivers could not recognize the meaning of the white cane.

His association continues to mark International White Cane Day with public awareness activities and invites traffic police to take part. They are also working to have white cane rules formally included in the national traffic laws.

He mentions a recent case where a blind man injured at the Seven Day roundabout reported the matter to traffic officers as part of ongoing consultations on improving the law.

Linda Poni Tartisio from the same association lost her sight in 2003 and works at the Union for the Disabled. She uses a white cane but still faces daily risks.

“I face challenges crossing both main and side streets because of motorcycles. If I have money, I hire a motorcycle to avoid the danger,” she says.

Linda notes that even with mobility training, poor traffic discipline continues to put visually impaired people at risk. She says many understand what the white cane signifies, yet visually impaired citizens still struggle to move safely along public roads.

For the deaf community, mobility concerns take a different form. According to Kachinga Peter, Chairperson of the South Sudan National Association of the Deaf, deaf pedestrians walk against the flow of traffic so they can see oncoming vehicles.

“We cannot hear if there is danger behind us. We rely entirely on our eyes,” he says through sign-language interpreter Jaklin Night Charles.

Kachinga explains that communication with authorities is often difficult because many traffic police officers have no sign-language training. As a result, deaf citizens struggle to report violations, accidents, or dangerous road conditions.

Across disability communities, the call is clear: South Sudan needs a more inclusive traffic system, with visible signage, enforcement of existing regulations, trained traffic officers, and consistent public education.

Advocates say safer roads for people with disabilities are essential not only for movement, but also for dignity, equality, and full participation in society.

With efforts underway to introduce white cane rules into traffic law and disability organizations seeking deeper cooperation with authorities, many hope South Sudan is beginning to move toward safer and more inclusive streets for everyone.