Summary:

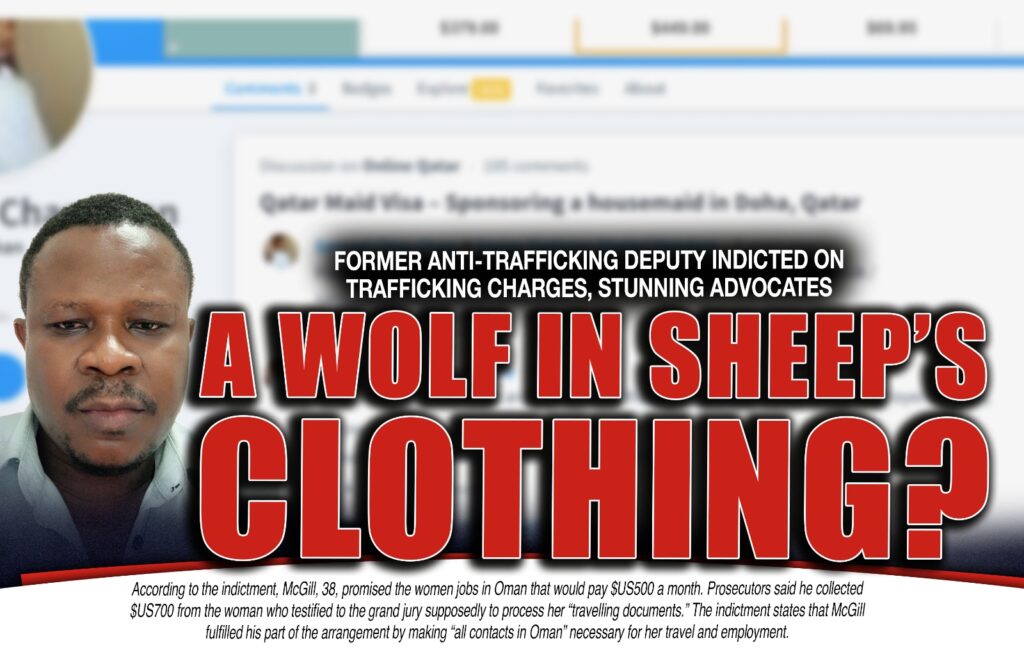

- In a development that shocked anti-trafficking advocates, a former assistant director of Liberia’s antihuman trafficking unit was indicted for allegedly trafficking three women to Oman.

- The accused, Henry McGill, is the highest-ranking government official to be charged in human trafficking. Experts said many more are likely involved.

- Prosecutors said the case was delayed because of victim intimidation. Anti-trafficking experts said government must urgently strengthen victim protection as cases move to trial.

By Anthony Stephens, senior justice correspondent with New Narratives

A former assistant director of the antihuman trafficking Unit at Liberia’s Labor Ministry has been indicted on charges that he participated in the very crime he was appointed to help combat.

A Monrovia grand jury’s decision to indict Henry McGill, who held the assistant director position under Labor Minister Cooper Kruah in the administration of President Joseph Boakai, followed more than nine months of investigation as key witnesses refused to testify saying they had been offered bribes and intimidated by people linked to McGill.

McGill is the most senior Liberian government official yet to be prosecuted for trafficking. He is the second Liberian government employee to face trafficking charges in recent years. Arthur Chan-Chan, a National Security Agency agent sentenced 25 years for trafficking women to Oman, was the first.

Adolphus Satiah, the former head of the anti-trafficking unit where McGill once worked, said he was stunned when he learned of McGill’s arrest.

“I didn’t expect that someone brought into the unit could have been involved in human trafficking, said Satiah, who was removed from the post when the Boakai administration took office in 2024, in a phone call. “It taints our record. But the government is doing the right thing. It sends a strong message that when traffickers are caught, they will be prosecuted.”

Only one of the three women McGill allegedly trafficked to Oman in 2022 appeared before the grand jury. Prosecutors say McGill earned $US21,000 from the scheme – part of his share of payments made by the women and their families who were told they were going to well-paying jobs or to study.

Prosecutors said it is possible the women were among many others trafficked to Oman as part of a major ring. But, they note, only three cases have been formally brought forward so far, because those are the ones for which investigators have gathered sufficient evidence.

As with many others, the women were not placed in a safe home when they returned to Liberia from Oman — where prosecutors said the conditions had been hellish. The women, they said, were ill-treated and made to endure long hours of work for their Omani employers, often without food and pay.

Prosecutors said additional witnesses—including the two remaining women, investigators and police detectives—are prepared to testify at trial. They expressed confidence that the expanded testimony will be enough to secure a conviction. The women’s names are being withheld for their security.

According to the indictment, McGill, 38, promised the women jobs in Oman that would pay $US500 a month. Prosecutors said he collected $US700 from the woman who testified to the grand jury supposedly to process her “travelling documents.” The indictment states that McGill fulfilled his part of the arrangement by making “all contacts in Oman” necessary for her travel and employment.

The indictment said that when the woman arrived in Muscat, the Omani capital, an unknown man who had her photograph on his phone identified her, seized her phone and travel documents, and instructed her to follow him to an office — a scenario similar to what other women previously told FrontPageAfrica/New Narratives about how they were trafficked. According to the indictment, the woman was then handed over to an employer identified only as “madam.”

The indictment said that while with her employer, she was “ill-treated like a slave,” worked long hours without pay, and was denied food until late at night. After several weeks, she refused to continue working and was returned to the agency’s office. From there, she was transferred to another madam, who made her work “tirelessly for months without any pay or compensation, under very stressful work and poor sleeping conditions.”

According to the indictment, the woman “cried, begged and pleaded to be sent to Liberia,” but her new employer demanded $US3,000, which she claimed to have spent to “purchase her.” Women are employed legally in Oman as servants under the so-called Kafala system, in which a migrant woman is employed under a two-year contract by an agent who handles her travel and placement. A household will pay the agent for the contract and will expect to be paid back if the woman leaves. Agents, who have invested in the woman’s airfare and other expenses, will then expect to be repaid by the woman.

Ultimately, the woman’s family paid $US500 to her Omani agent to secure her return. The government said its arrangements with the International Maritime Organization to fund her repatriation were close to being finalized by the time she arrived in Liberia.

Experts who helped secure the release and return of more than 350 women trafficked to Oman between 2021 and 2022 say they remain puzzled by the case of Arthur Chan-Chan. His brother, Samuel Chan-Chan, who is still still at large, and was last reported to be in Dubai, is considered one of Liberia’s most sought-after suspected traffickers. Judge Roosevelt Willie said he had approved the request of prosecutors for the Liberia national police to issue a red notice through Interpol arrest warrant for Chan-Chan in 2023.

Gregory Coleman, the inspector general of the Liberia National Police, told FrontPage Africa/New Narratives in a phone call that the foce was still awaiting from the court “the writ of arrest, the indictment and all the supporting documents needed to file the application for a Red Notice.”

“Once those documentations are presented that and we upload them into the system, the process will begin immediately,” Coleman said, speaking from the 2025 Interpol General Assembly in Marrakech, Morocco. The court disputed Coleman’s account, saying it granted prosecutors’ request for the documents in question in 2023— a point prosecutors later acknowledged. Prosecutors said they had begun the process of seeking an Interpol Red Notice for Samuel but failed to meet several requirements, including providing “the address of the person, the location of the person, the person’s photograph.”

A senior prosecutor, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said the process was further complicated by Interpol’s “difficulties in carrying out arrests and investigations in Arab nations such as Oman.”

Liberia’s trafficking networks are run through partnerships between local actors and foreign accomplices. Prosecutors say it is likely more government officials are involved. Nearly all cases involving Liberians—including those of Cephas Selebay, Arthur Chan-Chan, and McGill—have involved foreign links. Selebay, like Samuel fled after skipping bail. The pair are the only publicly known figures on record to have evaded prosecution despite being indicted.

Liberian prosecutors and anti-trafficking experts have repeatedly raised concerns about these networks. Experts say trafficking remains widespread in Liberia, driven largely by poverty and inequality.

Experts say that although trafficking on the scale of the more than 350 women sent to Oman may no longer be occurring, Liberians are still being trafficked. Recent U.S. State Department Trafficking in Persons (TIP) reports on Liberia — including the 2025 report released in September — note that traffickers continue to use different methods to carry out the crime “due to a lack of training, insufficient resources and staffing, and inconsistent application of victim-identification procedures.”

The report also noted that the “government had limited capacity to address trafficking crimes beyond urban areas, where inadequate resources and infrastructure hindered efforts.” As with previous editions, the 2025 report found that internal trafficking remains widespread.

McGill’s case brings to two the number of indictments state prosecutors have secured in recent months. Recently, they persuaded a grand jury to indict five women accused of trafficking their children and the children of relatives to Mali and Burkina Faso. Both cases now await assignment before proceeding to trial.

As the cases move toward trial, victim support has one gain become a central concern for frontline responders, as with previous trials. Princess Taire, social protection manager at World Hope International, said her focus is on the wellbeing of the women involved, including those expected to testify. She noted that many survivors of trafficking struggle emotionally and physically long after returning home and require sustained assistance.

“The care of handling them is my concerned,” said Taire. “Well need to give them the support they need. How are they prepared psychologically? How are they prepared physically? When you don’t have a witness; there will be no case. The government needs them to testify.”

In a recent Facebook post, the government said that 17 women who returned from Oman and were enrolled in a technical and vocational training program had graduated. Nuho Konneh, acting director of the anti–human trafficking unit at the Labor Ministry, told FPA/NN by phone that they were “preparing to enroll another batch of returned women into the vocational program.”

Konneh added that two safe homes—one in Bomi County and another in Montserrado—had been reactivated and were currently housing victims, a claim confirmed by activists working on victim protection.

This story is a collaboration with New Narratives as part of the West Africa Justice Reporting Project. Funding was provided by the Swedish Embassy in Liberia which had no say in the story’s content.