– Advertisement –

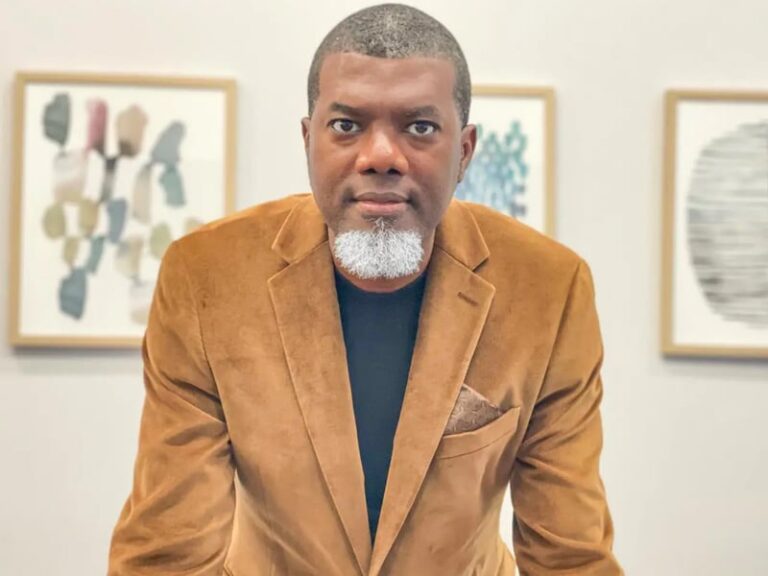

By Lt. Col. Samsudeen Sarr Rtd

Another dawn, another coup in Guinea-Bissau. At this point, the country changes governments the way some people change phone cases, frequently, impulsively, and usually after something cracks.

Wednesday’s military takeover, which unfolded with the usual mixture of gunfire, confusion, and soldiers casually strolling across the capital, fits neatly into the tired script of West African political instability. The presidential election is disputed, the two leading candidates both claim victory, and, voilà, the military suddenly discovers its patriotic duty to “restore order”. In truth, they were merely waiting for the politicians to hand them the excuse on a silver platter.

– Advertisement –

Guinea-Bissau did not earn the nickname “the Coup Laboratory of West Africa” by accident. This is its ninth coup or attempted coup since 1980. Nine. At this point, the only thing more predictable than a Bissau coup is the shocked reaction of Ecowas officials pretending they didn’t see it coming.

Just like Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, and Guinea Conakry before it, this latest drama follows a familiar pattern: the presidential guard, the elite unit supposedly handpicked to protect the head of state, simply turns around and escorts him out of power to prison.

It is the African political paradox of our time where presidents are toppled not by disgruntled generals far away in the barracks, but by the men stationed ten metres from the presidential bedroom. These guards know the president’s security lapses better than his medical doctor knows his blood pressure.

– Advertisement –

Why do African leaders keep falling for the same trap? Because instead of building strong institutions, they build strong personal guard units. And personal guards, as history repeatedly shows, remain loyal only until a better opportunity, or better offer, appears.

If Ecowas is a security guarantor, then perhaps I am the president of Zimbabwe.

Ecowas troops in Guinea-Bissau were physically present but politically absent. They stood by, eyes wide open, while the soldiers executed the takeover with the calmness of a morning parade. Ecowas peacekeepers were supposed to deter precisely this situation. Instead, they became background furniture in a military theatre.

This is not the first time the bloc has been exposed for overpromising and underperforming. After sabre-rattling over Niger with threats of military intervention, a drama that ended in nothing but embarrassment, Ecowas has quietly returned to its old habit of issuing a statement of “grave concern”, call for “restraint”, and then, will gradually accept the new reality until the junta hosts them for tea.

President Umaro Sissoco Embaló’s downfall also carries a regional lesson dressed in bright neon. It illustrates that leaders or governments do not outsource their national stability to another president who is himself subject to democratic cycles.

Embaló leaned heavily on former Senegalese leader Macky Sall for political and military cover. But Sall has since left office, and with his exit went Embaló’s safety net. Depending on another nation’s leader for your survival is like borrowing an umbrella during rainy season; the moment the owner walks away, you’re drenched.

In his absence, the only actors left with decisive force are the same ones who have rewritten Guinea-Bissau’s political order repeatedly, the military.

What keeps recurring in these crises is not mystery but mathematics. Africa’s security institutions tend to be stronger, more cohesive, and more disciplined than the political class. The politicians argue; the courts wobble; the electoral commissions confuse themselves; Ecowas hesitates; foreign allies vanish. And in that vacuum, the men with guns decide that they alone can restore order, usually by creating even more disorder.

Each coup weakens institutions. Weak institutions lead to more coups. And so the wheel turns, grinding away the little democratic progress made.

Guinea-Bissau carries scars from decades of instability, assassinated presidents, mutinies, drug networks, and civil conflict. For such a country, every coup is a risky dice roll. One wrong move and the country could slide back into violent fragmentation.

Let us hope, yes, hope, that this latest takeover does not unleash another round of factional fighting. But hope alone cannot cure chronic fragility.

Because at the end of the day, Africa’s enduring truth remains painfully unchanged.

A government that cannot control its own security forces does not govern; it merely rents power until the next uniformed landlord comes knocking.

The author is a former commander of the Gambian National Army and representative at the UN.